Chapter 5

Communicate the options

How effective communication helps business partners understand design

As mentioned in Chapters 3 and 4, increasing organizational trust is a matter of getting to know your business, your business partners, and aligning your work to viability. In reality though, those steps alone are not enough, because your partners are suffering from decision fatigue.

Decision fatigue is when the quality of decision-making deteriorates simply because there are too many decisions to be made. But designers can help the situation through effective communication.

The ability to communicate clearly is the single most important skill you can develop to mature decision-making in your organization and relieve decision fatigue. Effective communication helps your business partners better understand the opportunities and risks that design identifies.

For all the value they could create, too often designers appear naive in the face of genuinely understanding cultures of decision-making, of how an inability to generate political capital can undermine their ability to deliver change.

- Dan Hill, author of Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: a strategic design vocabulary

The first step to effective communication is to use languages and structures that are already valued by others. This will help gain trust and influence and lead to more support from business partners (rather than grievances). It’s only when that trust is gained that iterating on the language and structures themselves will be accepted.

This chapter focuses on communication. We’ll review alternative structures for:

- Storytelling

- Presenting

- Analysis

- Negotiation

- Gauging ambition

Identify valued storytelling structures

Designers, while particularly good at developing insights, need to improve how they communicate recommendations, risks, and trade-offs in order to activate those insights. In my experience, Post-its are not especially effective for these types of communications. Nor are sprints, workshops, or diagrams.

Quality trade-off decisions are made when partners understand opportunities, risks, and the choices available to them. Embedding the value of design within a valued storytelling structure is the way forward.

Valued storytelling structures provide familiar patterns of data, insights, and arguments for a plan moving forward. In using a storytelling method which already exists, we hope to:

- Increase the number of decisions made

- Establish trust

- Encourage cross-functional alignment

- Reuse what works

- Reduce formatting churn

If your organization doesn’t have a consistent structure driving decision-making, it can be frustrating. It’s also a good opportunity to borrow from counterparts in the consultancy space.

Add analytical storytelling to your toolkit

Over the last 10 years, narrative storytelling has become a mainstay in the designer toolkit. While wonderful for creating products that resonate with customers, narrative storytelling isn’t enough for making trade-off decisions. The purpose of narrative is to relate a series of actors, events, and actions to an audience through imagery. What it delivers in inspiration, it misses in expressing the reasoning of the storyteller.

To influence decisions, how a story is constructed is just as important as the narrative itself. In trade-off-decision scenarios, your partners need to know why you decided to tell the story in a particular way so they can better understand your rationale and argument.

Analytical storytelling

One of the main reasons organizations hire external, business management consultancies like BCG, Bain, or Accenture is because their analytical storytelling structure explains the rationale behind a recommendation. The structure is predictable and focused on prioritizing difficult decisions.

Analytical storytelling leverages both rational know-how and political understanding in order to present recommendations in a manner suited for a particular audience. It’s a powerful type of communication because it uses structured thinking with trade-off decision scenarios at the heart of the story.

Before diving into specifics on how to develop these types of stories, I have a few guidelines for when to use a narrative storytelling structure versus an analytical one. The guidelines are based on what you want to achieve with your presentation.

Use narrative storytelling:

- When you want your colleagues to connect with the customer perspective.

- When you want to inspire or motivate your organization to do something new.

- When your product team needs a compelling vision.

Use analytical storytelling:

- When you want to persuade your colleagues to fund an initiative or additional resources.

- When you want to inform partners of multiple paths forward to achieve an outcome.

- When you want to highlight the risks and opportunities ahead.

Use narrative AND analytical storytelling together:

- When you want your colleagues to see the value you’ve already delivered.

- Use analytical storytelling first, then narrative storytelling to connect the completed steps to the greater vision.

- When you want to highlight the risks and opportunities ahead.

Becoming familiar with a couple established formats will make you more comfortable participating in or leading decision-making activities with your partners. We’ll look at those in the next section.

Presenting with Pyramid Principle and SCR

When it comes to communicating business rationale, a great communication structure can make or break your presentation. One of the most famous and heavily used analytical storytelling structures is called The Pyramid Principle.

Developed by Barbara Minto, the Pyramid Principle takes the basic elements of a story and organizes them into a hierarchical structure to make them easy for someone else to understand. By using a pyramidal structure, presenters can present a progressive order to their arguments by framing what is known, summarizing logical reasons for action, and ordering the arguments in a way that makes sense to the audience.

The basic elements of an analytical story

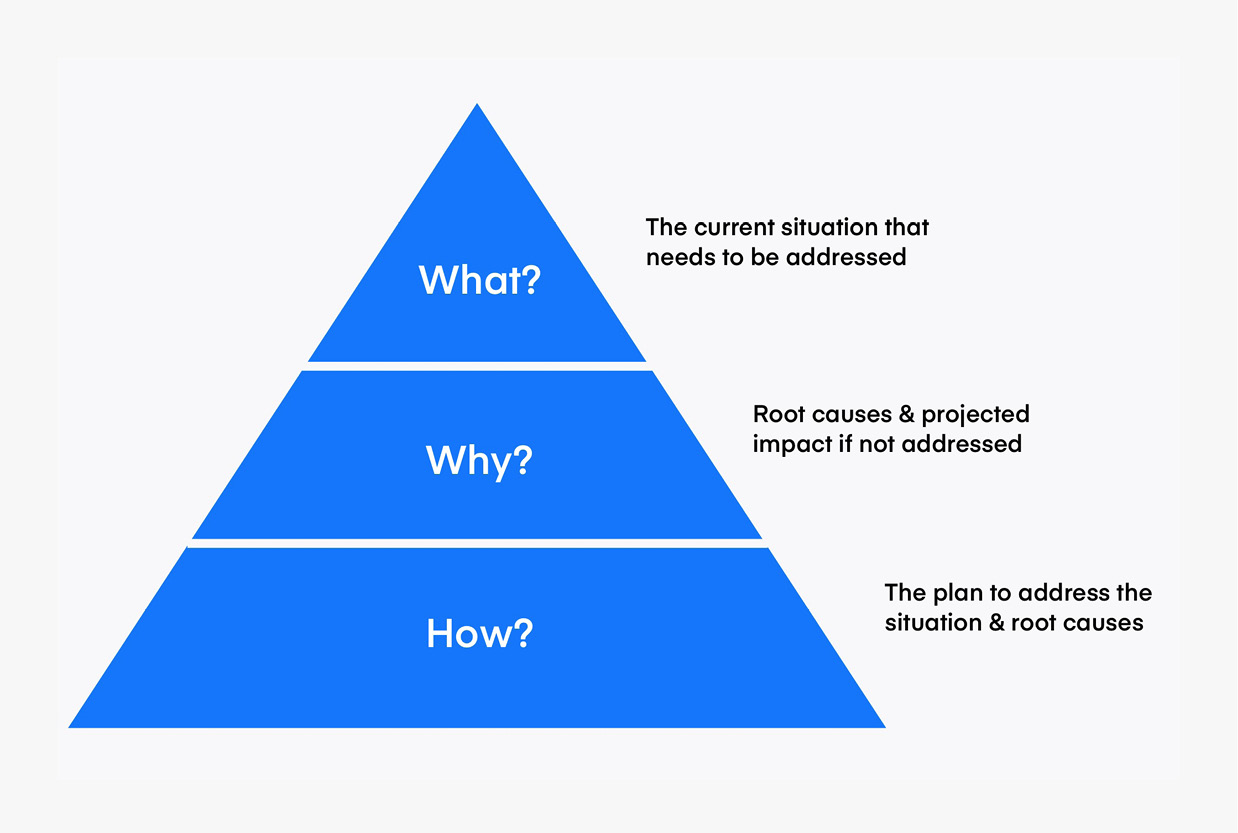

The pyramid shape introduced by Minto provides three basic elements of an analytical story: what, why, and how. Represented in Figure 5-1, the form gives structure to your thinking for a presentation, an email, or an analysis.

Figure 5-1: Structure your presentation with the SCR format

Figure 5-1: Structure your presentation with the SCR format

The pyramid is a tool to help you find out what you think. The great value of the technique is that it forces you to pull out of your head information that you weren’t aware was there, and then helps you to develop and shape it until the thinking is crystal clear. Until you do that, you can’t make good decisions on slides or video.

- Barbara Minto, Author, Educator, Creator of The Minto Pyramid Principle

From the top down, the pyramid forms the three basic sections and ensures that both your thinking, then your presentation, complete a thought before moving onto the next. By answering in the order of what, why, and then how, you present an analytical argument that your stakeholders can follow.

- What is happening? This first element frames an objective or problem that needs to be addressed. It’s important to start your story here in order to quickly confirm to others that you understand what the key objective or problem is. Typically, this is something all stakeholders are already aware of. If you see heads nodding when you talk about what is happening, that’s a good thing.

- Why is it happening? After summarizing what is happening, it’s vital to review the root causes and impact to customers and the company if the main objective or problem isn’t addressed. It’s in this portion of the pyramid where the majority of data, insights, and conclusions will be placed to support your argument.

- How are we going to fix it? This final section of the pyramid explains how the objective or problem will be addressed moving forward.

Now that you understand the basic structure of the pyramid, I’d like to share an example of an applied version of the structure. In practice, a commonly used version of Pyramid Principle is the Situation-Complication-Resolution (SCR) Framework. While there are other examples, this is a good starting point.

The Situation-Complication-Resolution (SCR) Framework

If you’re familiar with the 5 paragraph essay structure for writing, the SCR Framework is similar. The beauty of it is that it can be tailored for the circumstances of a specific decision.

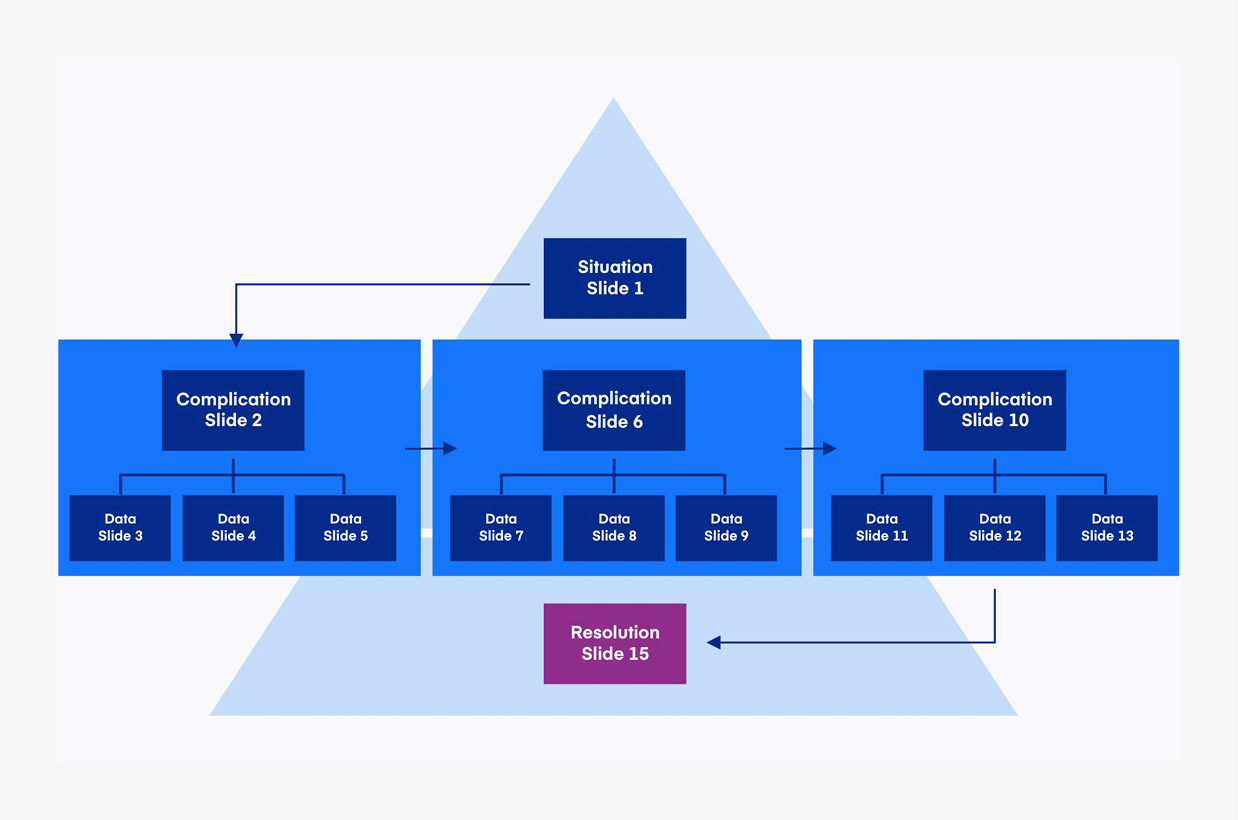

The framework allows you to structure your argument as a series of situations and complications, which leads to a resolution. The acronym represents the structure:

- Situation: The important, fact-based state of current affairs

- Complication: The reason(s) the current state of affairs requires action

- Resolution: The specific action required to solve the problem—the recommendation

The most basic approach for presenting business rationale with SCR is to highlight one situation, introduce three complications that require action, and conclude with a resolution to solve the problem. I like to think about it like an equation:

S+C+C+C+R = Business Rationale

From the pyramid structure, the situation is the “what,” the complications the “why,” and the resolution the “how.” With this basic format, a few best practice guidelines can help you develop a more complete SCR story.

Use the rule of three. The rule of three is a writing principle based on how we as humans recognize patterns. Since three is the smallest number of elements required to create a pattern, this principle suggests that using three elements at a time is more effective than using another number. An example of this principle in practice is using three complications to support the situation.

Complications should create tension. Without tension, stakeholders may be less than compelled to act. While design tools like Journey Maps and Service Blueprints are incredibly powerful for developing insights, time and time again I see designers fail to create enough tension from these tools to compel hard decisions to be made.

Support one complication before introducing another. Another mistake I see in presentations is the misordering of slides. Each complication should come with supporting arguments before introducing a new complication. Using the rule of three, include three supporting arguments for every complication. This is essential to both introduce and close a complication, ensuring your audience is able to follow along.

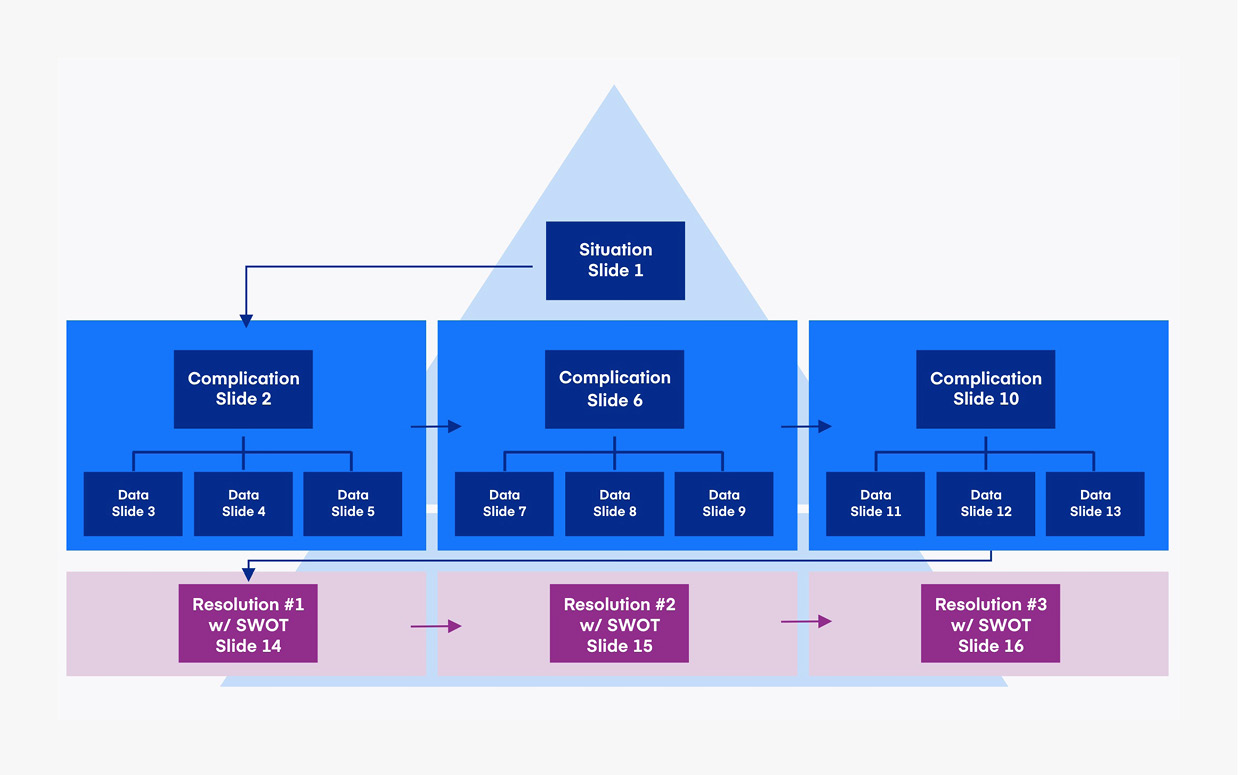

The real power of this framework is translating the structure into slides. The format tells a story where each page answers the question: “And so what?” In figure 5-2, the progressive order of the story being told follows the pyramidal shape, ensuring each part of the story connects with the business rationale.

Figure 5-2: Structure your presentation with the SCR format by Ryan Rumsey

Figure 5-2: Structure your presentation with the SCR format by Ryan Rumsey

Pro tip

When creating a presentation using SCR, fill out the header of each slide first. Each header should represent a situation, a complication, a supporting argument for a complication, or the resolution. This provides the story with a clear structure before you find the appropriate data to support each slide.

As you become familiar with the approach, you’ll find it’s applicable for more than just product or design decisions. Here’s an example from my past, where I used the SCR Framework to present my decision to change the priorities of my team. I modified the structure to include three situations, three complications, and one resolution: S-C-C-C-R.

- Situation: Cultural transformation is needed to drive improved decision-making across empowered product teams.

- Complication #1: The definition of design is based on the previous business strategy.

- Complication #2: An alternate Product Management process is not a top priority.

- Complication #3: Headcount has been significantly reduced with no plans to backfill at this time.

- Resolution: Shift the focus of the design team to build future business models while collaborating on existing products in a support role.

This example allowed me to present my argument as an analytical story and resulted in a quick, “sounds good, thanks for the update” response from my boss.

While many problems can be presented with this basic SCR format, there are situations when stakeholders may disagree, have a bias towards a specific solution, or simply want to have a say in the resolution itself. By introducing alternative scenarios as resolutions, you can adjust the story accordingly. In the next section, I’ll show you how to do that.

Identify scenarios with SWOT and SOAR

When organizational trust is high, the traditional SCR format works pretty well. Your audience will generally accept your resolution and the format helps build conviction around it. In circumstances where organizational trust is still an issue, a hybrid approach to SCR often works better.

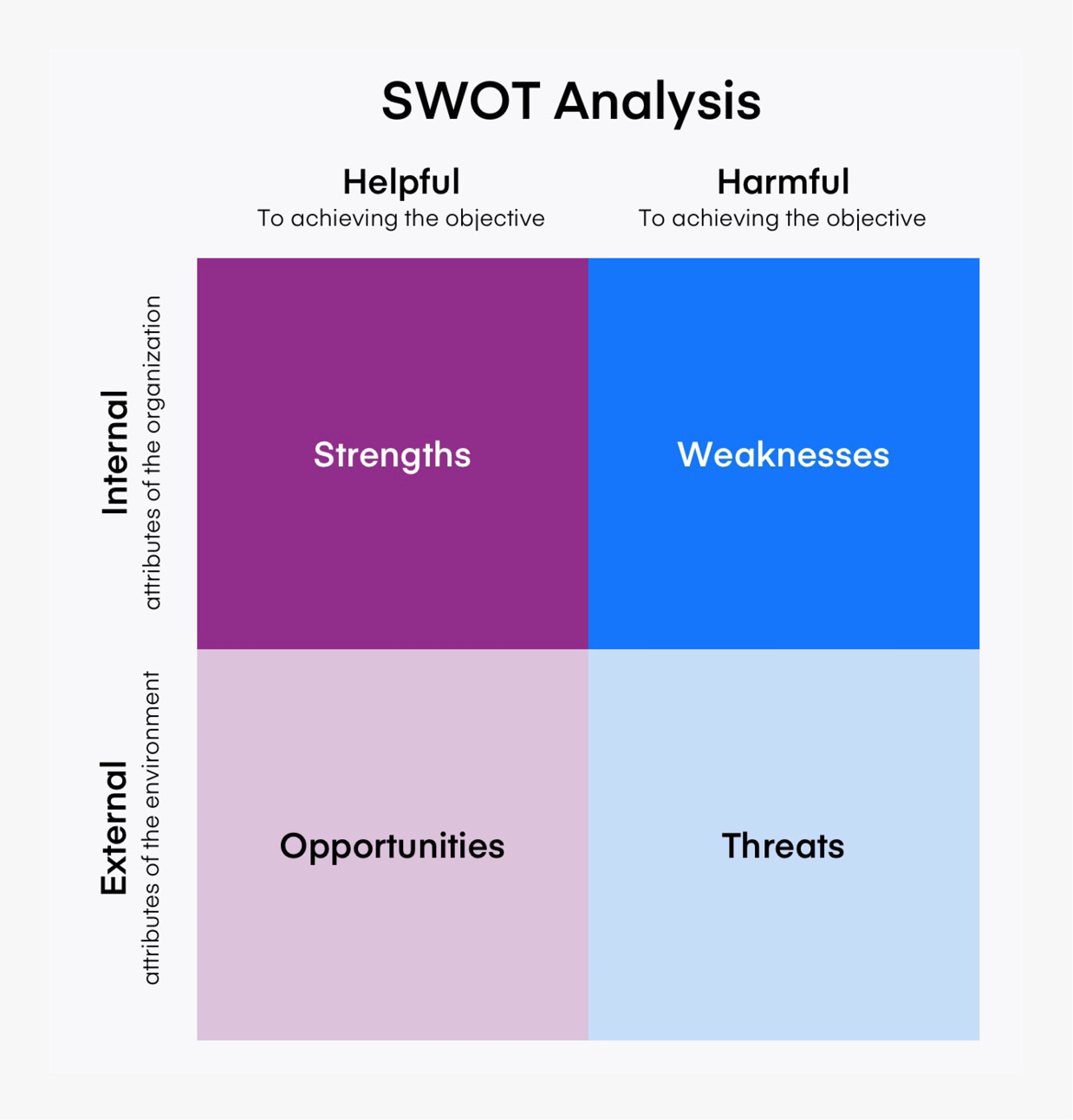

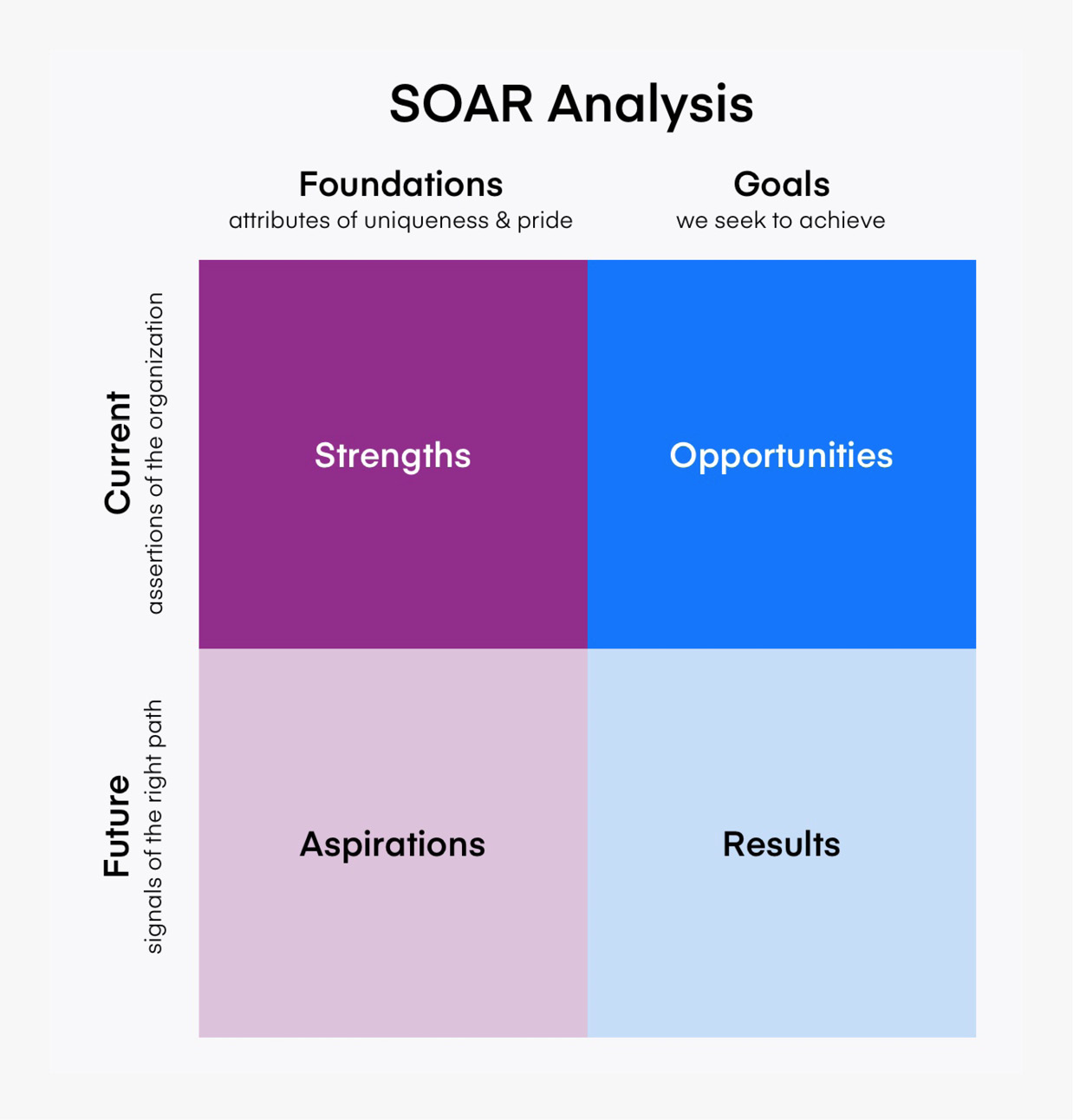

The hybrid approach I recommend incorporates two analytical frameworks used to present multiple scenarios as possible resolutions. SWOT and SOAR are good for highlighting the opportunities and risks of potential solutions, which increases the level of confidence to prioritize next steps. These acronyms may be familiar to you, but as a reminder, here’s what each stands for.

SWOT - An analysis used to identify the key internal and external factors important to achieving an objective. SWOT stands for: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. Visualized with a 2x2 grid (see figure 5-3) the analysis focuses on the internal strengths and weakness of an organization and the external opportunities and threats presented to an organization. SWOT is a well-known structure commonly used inside large corporate environments.

Figure 5-3: SWOT Analysis 2x2 grid

Figure 5-3: SWOT Analysis 2x2 grid

SOAR - A stronger option for smaller, less-developed organizations, SOAR stands for Strengths, Opportunities, Aspirations, and Results. The main difference between SOAR and SWOT is a primary focus on the positive end of the spectrum. SOAR (see Figure 5-4) analysis covers the asserted strengths and opportunities of the current state of an organization, as well as the future aspirations and results that drive organizational action.

Figure 5-4: SOAR Analysis 2x2 grid

Figure 5-4: SOAR Analysis 2x2 grid

By incorporating SWOT or SOAR analysis into your analytical storytelling, the pyramidal shape continues to support the narrative as new types of resolutions are presented. In figure 5-5, the only elements that change are the resolutions. Rather than one answer, scenarios allow you to present multiple options moving forward. I’ve found this structure incredibly helpful to getting alignment quickly when multiple stakeholders are involved in a decision.

Figure 5-54: The SCR slide structure with SWOT analysis resolutions by Ryan Rumsey

Figure 5-54: The SCR slide structure with SWOT analysis resolutions by Ryan Rumsey

Trust is the all important factor to gauge whether or not you should include scenario analysis in your story. This is where lessons from Chapter 3 and 4 come in handy. When you’ve matured your understanding of your business and your business partners, these simple tips can help you determine the ideal structure: If you’re working with partners who trust you, use the SCR structure.

If you’re working with partners who want to be heavily involved in the decision, include SWOT or SOAR analysis as part of the resolution step. Present multiple alternatives which show the pros and cons of each, while ensuring that you highlight your recommendation.

If you’re working with a devil’s advocate, start with SCR. But when they chime in, be ready with SWOT or SOAR scenarios: “I’m glad you mentioned that Todd. We looked into that and here are the scenarios we worked through. If you have any additional information that would be helpful, we’d be happy if you could share.”

Pro tip

SWOT and SOAR analysis are two of the most effective ways to communicate experimentation results. In the real world, there are multiple paths teams can take to achieve a goal. Using either of these frameworks helps leadership teams feel more confident in making a decision moving forward.

Every decision has opportunities and risks. Scenario analysis communicates where you believe risks should be taken and what rewards are worth it. To align on scenarios you can live with, it’s imperative that you present arguments effectively. Using these frameworks, you’ll not only track decisions made, but be able to track the rationale behind those decisions.

Even when you have the supporting data and make a strong presentation, there will be times when things don't go the way you want them to. This is when understanding the ambitions of your colleagues is important. It's also helpful to plan ahead for how you will negotiate if discussions get intense. That’s coming up next.

Gauge ambition and plan for negotiations ahead of time

There's a strange dance that sometimes takes place among decision-makers. Unspoken agreements are made, unexpected outcomes are presented as new ideas, and designers are often pushed to the sidelines while fates are decided. I call this the negotiation zone, and we need to be prepared to assert ourselves.

Let’s face it, the majority of design decisions involve negotiations. From my experience, the majority of trade-off decisions also come after a negotiation and to become a successful negotiator, you need to focus on three things:

- Empathize with your partners to understand their mindsets, motivations, fears, and goals.

- Do your best to remain objective. Use objectives, measures, and experimentation to support your position, rather than your emotions.

- Prepare, prepare, prepare. Studies have shown successful negotiation is 80 percent preparation.

We’ve already covered #1 and #2 in this book. To prepare for a negotiation though, you have to consider what you’re negotiating, where you’ll hold your line, and what you’re willing to give up. The Negotiation Canvas is a great tool to help.

The Negotiation Canvas

Developed by Pablo Restrepo and Stephanie Wolcott of Negotiation by Design, the Negotiation Canvas uses the familiar constructs of other canvas tools in the designer’s toolkit. Using the Negotiation Canvas, you can better prepare for your next negotiation with a partner, client, or stakeholder.

The canvas itself focuses on two separate positions: yours and that of the person with whom you’re negotiating. Within the structure, designers can prepare for negotiations by capturing desired outcomes, bargaining chips, and walk-away alternatives.

Figure 5-65: The Negotiation Canvas from Negotiation by Design

Figure 5-65: The Negotiation Canvas from Negotiation by Design

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of the canvas framework is that it forces designers to consider the point-of-view of the person with whom they’re negotiating.

Pro tip

Be the first to act in a negotiation. By setting the bar up front, you can gain a psychological competitive advantage. Referred to as anchoring, being the first to act can establish a cognitive bias when an individual depends too heavily on the initial offer (considered to be the “anchor”) while making a decision. Being first won’t work every time, but the science is on your side.

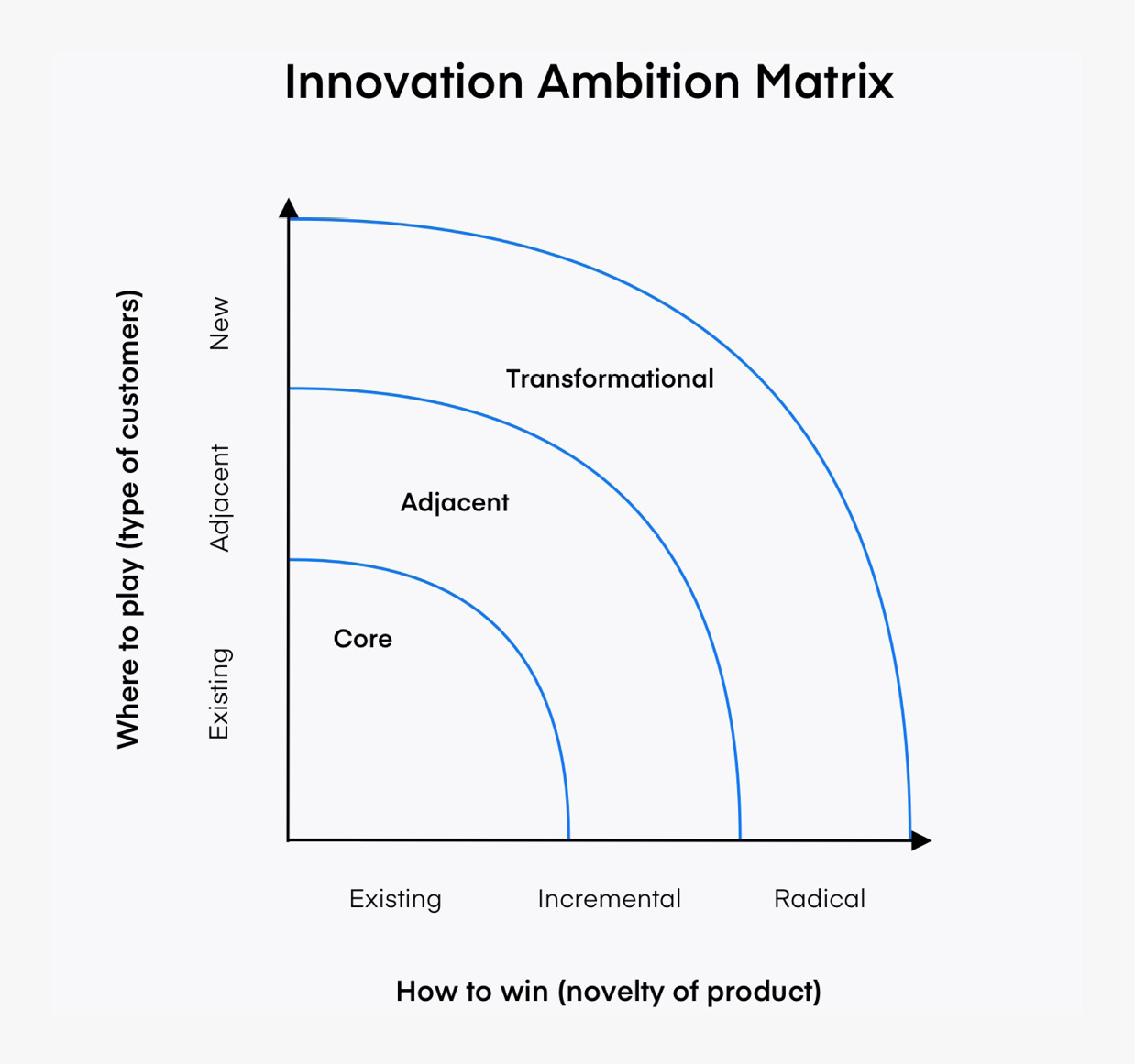

The Innovation Ambition Matrix

While preparing for a negotiation is crucial, in my experience, many occur because stakeholders or team members are not aligned on how ambitious each wants to be with a project or plan. To best gauge this ambition, there’s a fantastic tool called the Innovation Ambition Matrix.

Introduced by Bansi Nagji and Geoff Tuff at the Monitor Group, this tool is primarily used to unify and balance the innovation efforts inside an organization — but I’ve found it to be very helpful for products as well. It helps clarify where cross-functional partners “think” the organization is playing and how everyone expects the organization will win.

The matrix itself is based on a graph with “How to Win” on the x-axis and “Where to Play” on the y-axis. From a product standpoint, “How to Win” can be any of three types of products in an organizational portfolio: existing, adding incremental features, or developing something new (radical). “Where to Play” points to the types of customers the product will serve: existing, adjacent, or a new customer market.

With this graph set up, the primary goal of the Matrix is to determine how ambitious cross-functional partners want to be. There are three levels of ambition:

- Core: Optimize current offerings

- Adjacent: Add new features

- Transformational: Create new products

Figure 5-7: The Innovation Ambition Matrix from Monitor Group

Figure 5-7: The Innovation Ambition Matrix from Monitor Group

The best times to measure ambition are at the beginning of a project or when workshopping new ideas. In either scenario, I take the following steps to complete the activity:

- Draw the grid.

- Assign Post-it colors to cross-functional partners.

- Ask each partner to capture the projects or features in the backlog on Post-its.

- Place Post-its on the grid according to how ambitious they believe the team should be with each.

- Analyze any deltas that show up on the matrix and use those to find an agreed level of ambition moving forward.

Pro tip

The Innovation Ambition Matrix is a fantastic activity for getting alignment and buy-in with a design system. Since a design system can range in complexity, getting clarity on ambition proves a valuable exercise before committing resources to creating or updating it.

This Innovation Ambition Matrix is so simple, yet so helpful to getting partner alignment up front. When approached as a cross-functional team activity, a completed matrix is a wonderful way to negotiate before the stakes are too high and emotions get involved. It’s the perfect tool to share with your industry friends.

Conclusion

Communicating well is a key for influencing business decisions and outcomes. By adjusting your communications, designers can show their business partners that they’re capable of working in multiple ways, as well as prepare for any difficult decisions.

In the final chapter, we’ll take the lessons learned thus far and show how you can put them all together. The goal is to help you mature your approach, which in turn will help mature design in your organization.

Further reading

- 5 steps to find stakeholders and key collaborators who will champion your ideas.

- The rule of three by Brian Clark, Copyblogger founder and host of Unemployable

- How to Tell a Business Story Using the McKinsey Situation-Complication-Resolution (SCR) Framework by Jeremey Donovan, SVP of Research & Advisory Services at CB Insights

- The Pyramid Principle by Ameet Ranadive, Chief Product Officer at GetYourGuide

- The Negotiation Canvas download from Negotiation by Design